Peter Stevens discusses the design and development of the New Lotus Esprit X180

''I was nervous of what Giugiaro would think,'' says Lotus chief designer Peter Stevens, reflecting on the reaction to his redesign of the Esprit. ''Charmingly, the first time I met him after its public launch he gave me a big cuddle and said: 'Ahhh, perrr-fect'. He was extremely gracious." Giorgetto Giugiaro was responsible for the original Esprit. The star of the 1972 Turin Show, this styling exercise on the Europa chassis became a production car within three years. It was on of the great designs of the '70s but, 10 years after its launch, the Esprit's folded-paper looks were beginning to date alongside the more organic forms of the '80s. Aware of this, Lotus chief executive Mike Kimberley saw that the reskinning job was necessary to extend the Esprit's life. Part of the trouble with the car was that its design purity had been lost over the years. The leap in performance brought by turbocharging had made extra cooling and downforce demands, causing the Cd to slip from the original 0.35 to over 0.40. Stevens' boss, design director Colin Spooner, agreed that something new was needed: "The old Esprit was a classic in its productions, almost destined to last forever, but the various stages of engineering development had required bits and pieces to be added on, to feed in more air or generate more downforce. These had not been given sufficient design thought, so the car had begun to look tacky."

A rendering from 1984

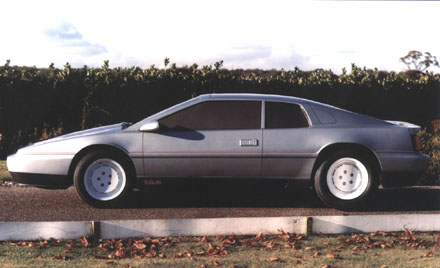

Clay model of the Esprit X180

The brief for the redesign came down from on high at the same time as Stevens was turning a freelance association with Lotus into a full-time job. Working alongside Spooner, he began preliminary sketching in October 1985 and produced a clay model soon after Christmas. In true Chapman tradition, the project began as a quiet little operation on the sidelines, with no more than two or three other people aware of what was going on. Other senior Lotus personnel, including some of the directors, first learned about the new Esprit only when a full-size glassfibre mock-up was finished just five months later, in February 1986. This coincided with GM taking a controlling interest in Lotus.

A rolling prototype of the new Lotus Esprit at Hethel on 1st November 1985

"We found ourselves usefully placed to encourage GM with the news that we had an Esprit replacement waiting in the wings," says Stevens. "Mike Kimberley gave us the task of telling them how soon it could be available for production, and then gave us that optimistic estimate as a deadline. It inspired everyone to put a lot of effort into it. "I started work with a fairly clear idea of what I was aiming for. Giugiaro's design had so much that was good, so I knew that I should not be seen to be throwing any of it away. Nothing about it can be criticised.

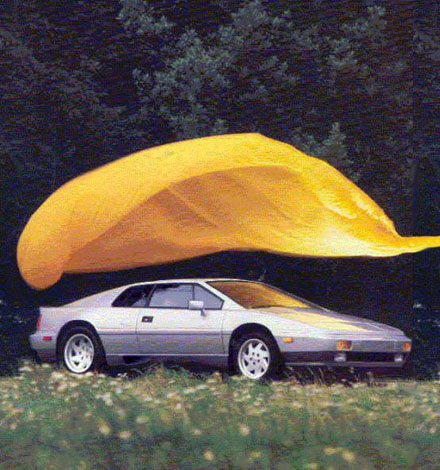

Side profile of the Lotus Esprit Turbo

There was a feeling about its proportion which we wanted to keep, because of it's 'Lotusness'. At the same time we were in an important stage of transition because of GM's arrival, and this was a great opportunity to show the world that we were still Lotus, not a GM subsidiary. "I didn't do weeks and weeks of sketch work. This kind of car needs to be an immediate statement which is then refined. I wasn't groping for a solution, so nothing would have been gained by drawing 50 or 60 totally different cars. All of us here have a good idea of how a Lotus should look, so that gave us a start. A lot of discussion took place before I produced the renderings, so the early drawings look very close to the finished car."

Wheel proposals by Julian Thomson, final choice was a mix between left and right. Only 15 months elapsed between approval of the basic design and the beginning of production. Larger car companies might need five or six years to achieve as much, but at Lotus the pressure of a deadline, the intimacy of a tight ship and the buoyant morale which infuses the place seem to make anything possible. Just as Pininfarina was sufficiently fired up by the Ferrari F40 to deliver the design within a year, a small core of gifted people at Lotus made the new Esprit happen on a mixture of adrenaline and purpose. "We try to achieve more while using less," says Stevens. "We can extract more out of available resources than other companies. That's why we can do things quickly, and why we get more spirit and character into our cars. Maybe there are rough edges, but the cars come out fresher and more immediate. There was no point at which I felt a lack of confidence in the car and went back and fiddled with it. Time was tight, so I had to be pretty sure I felt comfortable with the way it looked."

Colin Spooner

Colin Spooner ". . . my brief was that we required a more modern and sophisticated shape but with no requirement for change to the basic mechanics. This was a tough proposition, but in this case was aided by the excellent proportions of the original design . . ."

Peter Stevens, the Design Team and Colin Spooner with the Federal Lotus Esprit in 1987

There is more to Stevens' Lotus Esprit than a new skin. Although its basic wheelbase and track dimensions are unchanged, it is now more simple to manufacture. Different versions of the old Esprit were made with three sets of body tools, because of the different generations in which the unblown Esprit, the UK Turbo and the Federal Turbo were developed. Right from the start the new car had to be built from one set of tools and moulds: it was developed around the best of the original versions - the Federal Turbo.

While the departure from the original shape is no more than a couple of inches at any point, the whole is far more co-ordinated. Sharp edges have been replaced by curves and the corners pared off. The car has been generally slimmed down rather than fattened up, even though the original brief enforced plenty more restraints than merely sticking to the structural dimensions. The A-pillars and door frames had to remain, the same wiper mechanism had to be used (thereby limiting scope for putting curvature into the old flat windscreen) and the interior could not change.

A welcome - and unexpected - bonus from the more rounded shape is improved stiffness. Refinements in body/chassis engineering contribute, but the softened edges distribute loads over a broader surface: Stevens believes that the old car's sharp edges used to behave rather like hinges when the body was stressed during cornering.

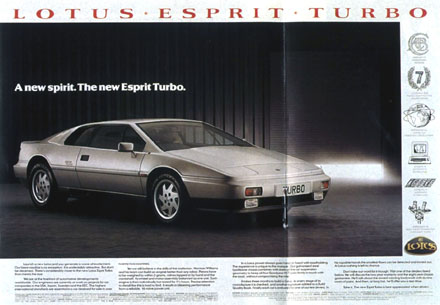

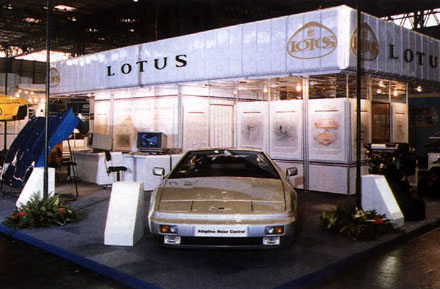

The new Lotus Esprit Turbo Exhibited in 1987

Click on picture to enlarge

Cost constraints imposed limitations in componentry, because Lotus, like all other small-volume manufacturers, has to wheel a supermarket trolley around other manufacturers' parts bins. Spooner acknowledges that mistakes have been made in the past, citing the old bogey of using Marina door-handles (ironically, these were Giugiaro's design for the Morris Ital). There was a determination with the new Esprit not to let bought-in bits spoil the integrity of the design. "Tail lights are a good example," says Stevens. "Tooling and homologation of unique tail lights would have cost more than the budget for the entire car. My feeling is that small volume manufacturers tend to produce a shape they like, then go grubbing around for tail lights to bung on it. I started with a decision on tail lights" - from Toyota - "and really designed the car around them to prevent them looking incongruous. I think they are comfortable with the car." Working as a stylist is a larger job at Lotus than it might be elsewhere. Instead of signing it off when he was happy with the shape, Stevens found himself involved for the first time in his career at the sharp end of getting a design through to manufacture. As Spooner says: "Peter quickly discovered that you cannot afford to turn your back for a minute, because somebody removes one of your design subtleties". This occurs because some interpretation and initiative by production engineers in translating the mock-up into tooling. The process can happen quickly when the heat is on: the designer's idea becomes a tool one day and a component the next.

The new Lotus Esprit Turbo Exhibited in 1987

Click on picture to enlarge

Stevens suspects that the first pattern for the sills was done when he was away from the factory for a day. He had carefully shaped ducts on each side to echo the lines of the rear side window, but someone decided that moulding the apertures in this way was impractical and produced tooling for a cruder version. The precise shape eventually came out as Stevens planned it, but one piece of tooling compromise did get through while his back was turned. The fuel filler flap on his mock-up had radiused corners, but the subtlety is lost on the sharp-cornered flap of the finished car. "I considered it vital to hang on to all my little details because each part of the car was designed to contribute to the whole," he says. "A customer would never notice the edge of a duct being vertical when the angle was intended, but he might get the impression that the car is not quite harmonious, without knowing why. This idea always makes me think of the Marcos: it looks quite wild when it zooms by, but when you see it parked it looks untidy."

Understanding the manufacturing aspects of design enabled Stevens, along with engineering staff, to refine the technique for joining the upper and lower halves of the body. His determination to remove the black strips which covered the joint on the old Esprit (and the current Excel) resulted in new manufacturing precision and a better method of making the bond. Turning the joint through 90 degrees means that it is tucked under the body colour side rib, in effect out of sight. Stevens says: "This showed us that we could treat grp as an engineering material, not a dinghy-making material". Pushing body-making processes forward has apparently had important implications for the new Elan.

While the initial brief had been to keep the old Esprit's interior, Stevens felt strongly that it should be changed. In making his case to Kimberley, he argued that it would be foolish not to take advantage of the extra interior space gained from putting an inch more crown into the roof. "We bullied him at a late stage into letting us have a startlingly small amount of money, " says Stevens. "You couldn't buy a Sierra Cosworth with it. The basic structure had to remain, but it needed to be softened, in keeping with the exterior. We kept the binnacle because it is a distinct part of the Esprit's identity, but we wanted to get some recline on the seats. Without major tooling changes, we cunningly engineered new seats which pivot at an unusual break at the lumbar point. The door trims and centre console were also better integrated."

1988 Lotus Esprit Turbo advert

The best modern designers have such a good feeling for aerodynamics that wind tunnel analysis should produce few changes. So it was with the Esprit, fine tuning being confined to tiny modifications at front and rear to improve aerodynamic stability. Trading drag to err towards negative lift at both ends gave the appropriate resistance to side wind changes. Stevens says that a 0.30 Cd could have been achieved, but dropping to 0.32 has been worth the gain in satiability. As soon as his revised Esprit was completed, Stevens turned to the M100. His reputation has been made with the Esprit: can he do better still with the new Elan?

A Federal Lotus Esprit Turbo

Autocar, May 1989 by Mark Hughes