GREAT

BRITISH SPORTS CARS

Lotus Esprit

Classic Car May 1996

Colin

Chapman ‘s flair and vision produced the remarkable Lotus

Esprit 21 years ago.

Though impaired by cash problems, it grew into one of the true greats,

says Tony Dron

As

a driver, it’s hard not to love this car in true Lotus tradition

it became a great driving machine, with extraordinary roadholding

and an unusual subtlety of handling. There’s a strong feeling

of real racer about it.

It’s incredible that it came into being at all In the early

Seventies, Lotus dropped all its established models to move upmarket

with the totally new Elite, Eclat and Esprit, all to be powered

by new all-Lotus engines. The idea was to produce a range of supercars

at bargain prices by employing modern manufacturing methods.

As Lotus got stuck into the practical work of this very ambitious

new era in its history, it became increasingly clear that the new

generation of cars would have to cost much more than planned. Meanwhile,

income was interrupted and, with the general economy far from healthy,

Lotus was frequently on the edge of financial disaster through those

years. Only the determination of Colin Chapman and his team kept

the company alive. After launching the Elite and Eclat in 1974 and

1975, they had great difficulty in finding the means to turn the

third new model, the Giugiaro-designed Esprit, into a practical

road car but the Italian stylist’s personal commitment helped

to keep the project moving.

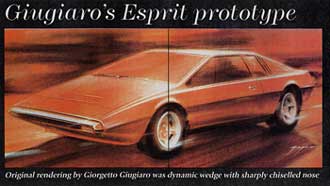

Against the odds, they made it For once, a fantasy show car was

put into production: Giugiaro’s styling exercise appeared

at the 1972 Turin Show and the production version was unveiled in

late 1975. We know now that early cars were inadequately developed

but the Esprit was on the road, Effective development and inspired

restyling over the years allowed it to endure.

There’s more to this than looks. A key point of the lasting

appeal of the Esprit must be the mixture of passenger car engineers

and race team personnel who worked on it. This produced a remarkable

machine — but not, for sure, without some (well glossed over)

internal technical arguments in the early years.

The Esprit had its faults but from the start it had the vital ingredient

of being exciting both to those within the factory and to the world

outside. In the gloomy days of the mid-Seventies it was invigorating

to see such a fresh, boldly executed, utterly modern sports car.

It was very close to Colin Chapman’s heart: he was determined

to produce it, whatever problems Lotus faced. When DeLorean wanted

to buy Lotus, the other -models were discussed but the Esprit was

always to be excluded so that Chapman could continue to make it.

By the late Seventies, however, Lotus cars were selling reasonably

well and the Formula One team was on top of the world. It’s

just a pity that Chapman ever met John DeLorean, let alone got involved

in saving his ludicrous 2 motor car from the perdition it deserved.

‘Lofty’

Dron does fit into Giugiaro Esprit, but only just: here he is at

the wheel of Chris Cole’s smart Turbo.

There’s much more room in post-1987 cars

BEHIND THE WHEEL

Before anything else is said, let’s be clear about one thing

the Lotus Esprit became one of the greatest drivers’ cars

ever made for the road. That is the simple truth of it. Early Esprits

were sensational but it wasn’t as easy to put a motor show

dream car into production as Colin Chapman probably thought. The

essentials were fabulous but a part-finished prototype car was put

on the market to get some money back before the company went under.

The dream was strong enough to make you want to love it but it was

a while before Lotus managed to eliminate the nightmare element.

When the new Esprit first arrived it was considered interesting

but not fast enough to deserve the tag of ‘supercar’.

The lack of performance is often overstated: to put it in perspective,

the standstill to 60mph accel-eration time recorded in Motor’s

Road Test of 1977 was 7.5 sec and, though maximum speed was not

measured, the magazine stated: ‘Over 130mph is probably feasible.’

True, these are not supercar statistics but they’re hardly

slow. Performance figures for the cheaper Triumph TR6. regarded

in the Seventies and since as a fast and powerful ‘real man’s

car’, were 117mph and 8.5 sec. Barry Ely’s Commemorative

S2, seen here, certainly did not feel slow on the road to me.

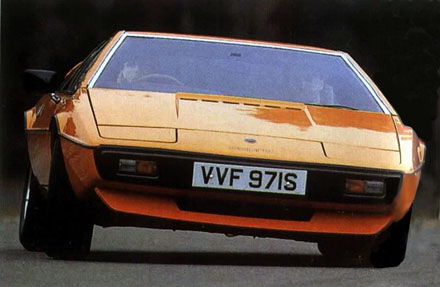

Lotus Esprit S1

Our

cover car, John Roberts’ S1 Esprit; note very Seventies trim

and Giugiaro badge. Most S1 cars went to the US. Engine cover was

only fitted to Series 1 cars; Wolfrace alloy wheels were also unique

to the early Esprit.

The earliest Esprits had phenomenal roadholding and simply astonishing

traction but the steering feel was below Lotus standards: worse,

the noise was enough to drive you mad, and there were several other

problems. But few British drivers ever experienced an SI, as virtually

all of them went abroad. Fortunately, the energy within Lotus was

such that the Esprit rapidly became good enough to own and live

with.

Performance was steadily improved: the normally aspirated 2.2 achieved

0-60mph in 6.5sec, with an estimated 135mph top speed: and the original

Turbo managed 5.6sec, with a claimed 152mph maximum.

The Esprit was greatly improved but some inherent faults remained

even with the introduction of the S3 and Turbo: these were mainly

bad visibility, especially to the rear, a poor heating and ventilation

system (despite many attempts, it took a very long time to get it

right), reflections on the screen (worse with lighter interiors),

small pedals which were too close together (excellent if you choose

the right shoes before getting in) and lack of headroom for very

tall drivers. Unusually elongated folk are more comfortable in the

earlier cars, which don’t have that extra ventilation outlet

by the left knee. Drivers of normal human dimensions find Esprits

comfortable, however, and while there are more practical and civilised

supercars from that era, for pure driving pleasure the Esprit is

a match for any and better than most.

Lotus Esprit Essex interior

The

experience of handling a mid-engined car with its engine mounted

longitudinally is rare enough: in an Esprit, the sense of balance,

surefootedness in the wet and feeling of control when driving fast

are strong sources of pleasure. You need to be something of an expert

to explore its high roadholding limit — but only because it

is so high. The ride is unusually good, too: with no lump of engine

ahead of you, it’s uncanny the way the front wheels handle

bumps and irregularities in the road. Lotus was always superb at

showing that lightweight, pure sports cars can be made to ride well

and the Esprit is an outstanding example.

Try to put aside any prejudice against four-cylinder engines. The

brand-new 1996 V8 unit looks magnificent and will, no doubt, lift

the Esprit into an even higher league — but, equally without

doubt, it will cost rather more as well. The four-pot engines in

all previous Esprits, normally aspirated and turbocharged, are admirably

light, efficient and enjoyable to use, if noisy.

Furthermore, the Turbo has unexpectedly excellent torque from low

rpm, with no sense of a ‘step’ in the curve as the turbo

‘comes in’; yet all Esprit engines are happy at high

engine speeds, too. Before electronic engine management was mastered

the quickest Turbos were rather ‘fussy’ but all blown

Esprits are firmly in the supercar performance league: the early

Essex of Paul Dewey, Graham Bedwell’s dry-sump model and Chris

Cole’s slightly later car all reminded me of that fact. They

are real road rockets.

When we were invited to visit the Lotus factory, to photograph the

cars in an appropriate setting, we were joined by Lotus engineer

James Grantham with his LHD Esprit from 1986, originally a US-spec

test car. He bought it some years ago and converted the engine to

UK spec. It’s one of the first with the Renault gearbox. which

replaced the old SM unit; it also has outboard discs. James says:

“It always amazes when I get back into it and drive. There’s

so much in reserve.

He’s right. All the owners agreed that you get used to the

restricted visibility and other negative points listed in the road

tests. Once you get behind the wheel it’s genuine supercar

pleasure at bargain price. Everything that really matters is evident:

serious performance. great steering, incredible roadholding. powerful

brakes with good feel, an unexpectedly good gearchange and the lithe

feel of a well-sorted racer. It’s not a ‘sensible’

car: it’s an escapist’s dream, and a fine one, too.

Fuel consumption is good for a Seventies car of such immodest performance:

in the region of 18-23mpg under hard use but 25-30mpg is easily

achievable. The normally-aspirated models. naturally, tend to be

the ones at the less thirsty ends of these ranges.

Don’t worry about the smell of resin remarked on in some road

tests. The bodies have fully cured now and there’s no trace

of any such odour. With the new body of 1987, visibility, headroom

and other longstanding flaws were substantially dealt with. It was

a successful reworking of the classic Esprit, recognised as one

of the greatest road driving machines. I it again... It’s

true.

DESIGN

Lotus

racing cars had long been mid-engined when the Europa appeared as

the first such L0otus road car in 1966. The idea was to offer an

exciting level of technology to enthusiasts at well below supercar

prices. The basic design of the Esprit, with a steel backbone chassis

and in-line mid-engined layout, may have been broadly similar but

the overall concept was quite different. Aiming for the big league,

the Esprit was therefore 13ft 9in long and 6ft 1in wide, making

it 7in longer and no less than 9in wider than the Europa. Furthermore,

the exotic Esprit was styled by the rising Italian star, Giugiaro.

The Esprit’s chassis differed from the Europa’s in that

the backbone stopped behind the seats. In place of ‘tuning

fork’ extensions to carry the engine, the Esprit chassis was

joined to a tubular structure at the rear. The rear suspension,

with fabricated radius arms, single lower links and fixed-length

driveshafts, was partly mounted on the gearbox. It was low in weight

but it transmitted noise and vibration to the interior. Spherical

joints were used in the rear suspension in the first few cars but

that proved unsatisfactory: bushes more suitable for road use were

adopted and all the cars were subsequently converted. Double wishbones

were used at the front, which was based on Opel Ascona parts.

Giugiaro's rendering of the Lotus Esprit

Long-term

supplies of the so-called transaxie gearbox/final drive from the

SM were secured from Citroen; a good move, as Lotus could not have

afforded to develop its own transmission. Crafty machining enabled

the inboard rear brakes to be fitted, too; the discs were solid

all round, with no servo-assistance at first, though that was changed

before long.

Lotus built its own engines at last, moving upmarket and away from

the old kit car image. The Esprit was always intended to be offered

with a choice of in-line four and V8 engines. For financial reasons,

the V8 Lotus engine did not materialise until this year. By the

time the Esprit arrived, the slant-mounted four-cylinder, double-overhead-camshaft,

aluminium engine was well proven in earlier cars. As first installed

in the Esprit in 1,973cc form, it ran on twin Dell’Orto carburettors

and produced 160bhp at 6,200rpm, with maximum torque of 140lb ft

at 4,900rpm. Although this equated to the efficient little motor

delivering an impressive 81bhp/litre, it could hardly be expected

to be enough to enable the Esprit to stand alongside the Ferraris,

de Tomasos, Lamborghinis, Maseratis and Porsches that it had been

intended to challenge.

Tony Rudd, Lotus’s engineering director at the time and one

of those charged with turning the Esprit from showtime dream into

practical reality, recalls running a prototype Esprit V8 on long-term

test in the Seventies: “Four litres and over 300bhp really

lifted the car but it tended to demolish second gear or break the

diff. When Lucas demanded payment for fuel injection development

we tried Webers but suffered fuel surge in corners.” Lotus

just didn’t have the money to finish the job: with reluctance

it had to drop it in 1979 and pursue an alternative path to true

high performance. By then the car had been in production for three

years.

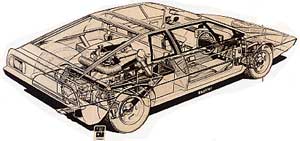

Cut Away of the Lotus Esprit S1

Esprit

bodies were made in two halves, joined at the waistline, but further

problems in 1976 had meant that the early ones could not be made

by the celebrated vacuum (VARI) system and were laid up by hand.

When the factory was able to go over to VARI, the Esprit put on

unexpected weight and, Tony Rudd recalls, “There was a bit

of a lull while that was sorted out.”

The first big change came with the S2, announced in August, 1978.

The main features were wider wheels, a bigger radiator with improved

airflow (but that took some months to reach production) and ducts

behind the rear windows (nearside fed the carb and demisted the

rear window; offside cooled the engine bay).

An engine enlargement to 2.2 litres, announced in May 1980, increased

the peak torque to 160lb ft at 5,000rpm and gave a useful performance

improvement. Also announced in 1980, after the forced abandonment

of the V8, the Turbo brought real performance at last. This engine

had been developed successfully and more cheaply in parallel with

the ill-fated V8: the Garrett turbocharger drove through smaller

twin Dell’Ortos and the fully redeveloped engine produced

210bhp. Early Turbo engines had dry-sump lubrication.

The rest of the car was substantially re-engineered, too, and the

normally-aspirated Esprit S3 of 1981 shared the main benefits of

this. There were changes to the appearance but the most important

developments were under the skin: a galvanised chassis with a wider

front box section and suspension mounting points; new engine mountings

to reduce vibration; pure Lotus parts to replace the Opel elements

in the front suspension; improved rear suspension with lower wishbones

and a new upper link. Designed for the V8, the production Turbo

was, frankly, over-engineered by Lotus standards. Torsional rigidity

was well up, vibration was down and there was a claimed, and much

needed, 50% reduction in noise inside the car. Relieving the driveshaft

of having to function as the upper rear suspension link gave an

additional reduction in transmitted harshness.

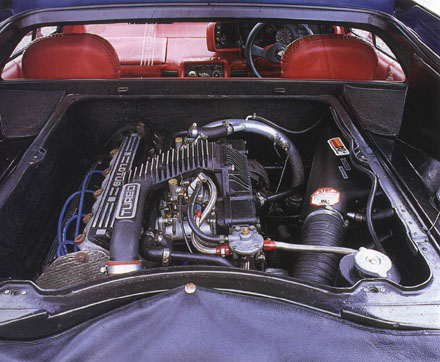

Lotus Turbo Esprit

These

changes, lavish new trim and luxuries such as electric windows all

cost money, so that, at £20,900, the Turbo Esprit was actually

more expensive than the rival Ferrari 308GTB, Porsche 911 SC Sport

and the rest — but it was also, at last, the quickest among

them.

Maximum power went up to 215bhp in 1986 when the High Compression

turbo engine was introduced but the increase in torque at lower

rpm was greater. Development went on without cease through the good

times and the bad.

Giugiaro’s classic styling was replaced in October 1987 by

a completely new, more rounded Esprit body, brilliantly styled in-house

by Peter Stevens. In 1989 charge cooling and electronically controlled

fuel injection boosted power to 264bhp in the sensationally quick

Turbo SE. That’s all recent stuff; but it’s worth stating

that the current Esprits are by far the best: noise, vibration and

harshness have been transformed, while drivers of almost any size

can feel comfortable. The transmission is now Renault, and modern

electronics and power systems abound.

The Esprit has been a true supercar for many a long year and the

arrival of the exciting new V8 completes the original design intention

at last, in a vastly more sophisticated manner than originally envisaged.

The charm of the early cars endures, especially from the 2.2 onwards,

and they remain the supercar bargains of the century in the classic-car

market.

OWNING & RESTORING

People

who do not own Lotuses say they are unreliable but the owners of

the Esprits shown here all said they have had no trouble. What does

this mean? First, there’s no doubting that years ago Lotus

frequently put cars into production before they were fully developed,

making early customers effectively unpaid test drivers. The firm

needed the cash flow to avoid bankruptcy.

The saving graces were always that Lotus cars were exciting to look

at, uniquely rewarding to drive and conceived with a fundamentally

elegant engineering philosophy. Chapman himself was extraordinarily

forward-minded and energetic. He thought fast, lived fast, paid

great attention to vital details and hated to waste time on anything

irrelevant. He designed all his cars for people like himself.

If you are the kind of person who forgets when your car’s

service is due, or deliberately ignores it in the hope that everything

will be all right, or can’t be bothered to let a turbocharger

cool down before switching off, you should get a Mercedes or a Morris

Minor. Don’t buy a Lotus: it’s not for you. When the

book says you should change this grommet at 5,000 miles and that

bearing at 10,000, it means it. The poor, neglected Mercedes or

Morris might roll on despite much abuse but the Lotus will not.

Stick rigidly to the service schedule, though, and you should find

that your Esprit is as reliable as those featured here: that’s

what the owners say, anyway.

Most Esprit owners prefer to rely on professionals to service their

cars but there are exceptions. Graham Bedwell enjoys doing his own

engine rebuilds and is very good at it, too, if his dry-sump Esprit

Turbo is anything to go by. Many home mechanics, accustomed to cast-iron

engines, would not take long to wreck a Lotus: excessive torque

settings when working on aluminium castings result in stripped threads

all round.

Turbo brought real performance at last in 1980, after V8 project

abandoned; 210bhp gave 0-60 figure of 5.6sec and claimed 152mph

There are things to watch out for. Some Esprits can catch fire if

the carburettors are worn out, allowing fuel to drip on to the distributor

with the inevitable result. Service everything when it is due; not

one mile later... If you need to replace a windscreen, it is a long,

tricky job, best tackled by a Lotus specialist. Much interior trim

has to come out and non-experts will almost certainly do some damage.

This tip came from Barry Ely, for 12 years the owner of the Commemorative

S2 seen here — guess what, it’s for sale and he’s

a Lotus specialist in Leyton, East London. To be fair, he points

out that screen replacement is not profitable — he just hates

to see Lotuses lashed up by bad workmanship and is happy to give

free advice to owners (call Barry Ely Sports Cars on 0208 558 3221).

Galvanised chassis were introduced with the S3 and the original

Turbo: so far all seem to remain as rust-free as the GRP bodies.

Some of the brighter exterior colours have faded but the mouldings

seem to be of excellent quality and extremely durable. The bodies

of the cars we photographed show no signs of crazing or cracking.

Good factory parts back-up means restoration is fairly easy. Obviously

an Esprit will be more expensive to rebuild than the average classic

but it’s a bargain by supercar standards: the four-cylinder

engines are a lot cheaper than the complex power units of exotic

rivals.

By the way, don’t fit silly wheels and tyres, or spacers.

Lotus took care to optimise its original specifications and such

nonsense won’t improve anything.

Wise owners belong to several Lotus clubs, gaining invaluable technical

advice and contacts from the most knowledgeable enthusiasts: there

are circuit-driving days to be enjoyed, too. One of the best this

year should be Silverstone GP Circuit (August 23, Lotus Drivers

Club). The cars shown here were located for us by Club Lotus, organiser

of many events throughout the year.

BUYING AN ESPRIT

For

the many reasons given elsewhere in this article, it is worth going

for a later car: Lotus really was struggling to survive in 1975-1976

and the relatively undeveloped S1s were, as a result, not that well

built. Oddly enough, the market hardly seems to recognise this:

a good S1 might fetch £5,000 or more while an early S3 in

similar condition might be worth £6,000. A younger S3 HC in

superb order might go for twice that much, however Good early Turbos

start from about £10,000.

Everyone knows that service history should be checked on any used

car. With an Esprit you need to know every detail, so don’t

rely on the sight of a fat file of ‘full service history’

documents. I’d read every one, carefully. Where has it been?

What went wrong? Was everything really done on time? Has it been

to any of the many respectable Lotus specialists recently? If so,

ring them up and ask what they know about the car.

S1s and S2s may need driveshaft and rear suspension work. An Esprit

that sits low probably needs new springs and dampers. Look for cracked

and corroded exhaust manifolds. Check the cambelt on all Esprits

(and renew it regardless if you buy the car — failure if it

snaps might do £2,000-worth of damage). Listen for transmission

whines, as gearbox rebuilds are not cheap. Check the radiators on

early Turbos, as unnoticed partial clogging can cause a burnt-out

piston at sustained speed.

If you can satisfy yourself on all these points, there is no doubt

in my mind that it could be worth paying a little over the guideline

prices. An early Esprit Turbo is the bargain supercar par excellence

in the classic-car market. One of its great rivals when new was

the Ferrari 308GTB: see if you can get a decent one of those for

10 grand now... Only the contemporary Porsche 91 ISC Sport comes

close in value for money today; some distinctly inferior contemporary

rivals mysteriously fetch about twice as much as the Lotus and the

(slightly more valuable but magnificently engineered) Porsche.

Buying a used example of any of these cars is a risk. Your first

service may cost thousands, so never buy on impulse. An enthusiast

I know snapped up an apparent bargain, an Esprit Turbo that had

suffered a minor engine-bay fire. In repairing that, it steadily

dawned on him that his car had been neglected for years and butchered

occasionally by cowboy mechanics. By the time he had finished putting

it all right, it looked superb and went very well but he was older

and wiser, and his enthusiasm was gone — he went back to Jaguars.

Look around the car to see whether it appears to have received loving

care. If it’s a dirty mess with even the odd stripped thread

on the engine, be very suspicious. If you can’t find a perfect

example of the Esprit you are chasing, a not-so-good one (a restoration

case, really) should be easy enough to find at £3,000-£4,000.

Do try to be realistic about what it will cost to get it back into

the sort of state that will stop poor Cohn Chapman from spinning

in his grave.

Don’t forget to check for accident damage before you close

a deal. Evidence of a shunt is easy to spot. If you find any signs,

get a professional inspection.

Cor,

look at that motor!” Esprit was a car to be seen in; this

one’s pictured with ex-Radio One DI, Mike Read.